Home Rules

of the Special Home

for Social Care

at Riebeckstraße 63

01 MAR 2021

In 1954, a home for social care was established at Riebeckstraße 63.[1] These homes were founded in the GDR in the mid-1950s and were the successors to the workhouses. The renaming was intentional to break the negative connotation with the workhouses.[2]

The homes were intended to house and care for people of legal age. Most of the people admitted had previously been convicted of “vagrancy,” begging, refusing to work, or prostitution. Women were often interned in the homes after a forced stay in a closed venereological ward, where women with suspected venereal diseases were forcibly admitted and forcibly treated.[3] The majority of those admitted to the homes for social care were women, often listed as “HwG persons” (“häufig wechselnder Geschlechtsverkehr”, frequently changing sexual intercourse).[4] From the 1960s, only women were placed in the homes.[5]

From 1961, the state closed the homes for social care throughout the GDR, as only a few people were still being admitted.[6] The Special Home for Social Care in Riebeckstraße, which can be regarded as the successor to the Home for Social Care, was probably established during this period.[7] Anyway, further research is needed to clarify these facts.

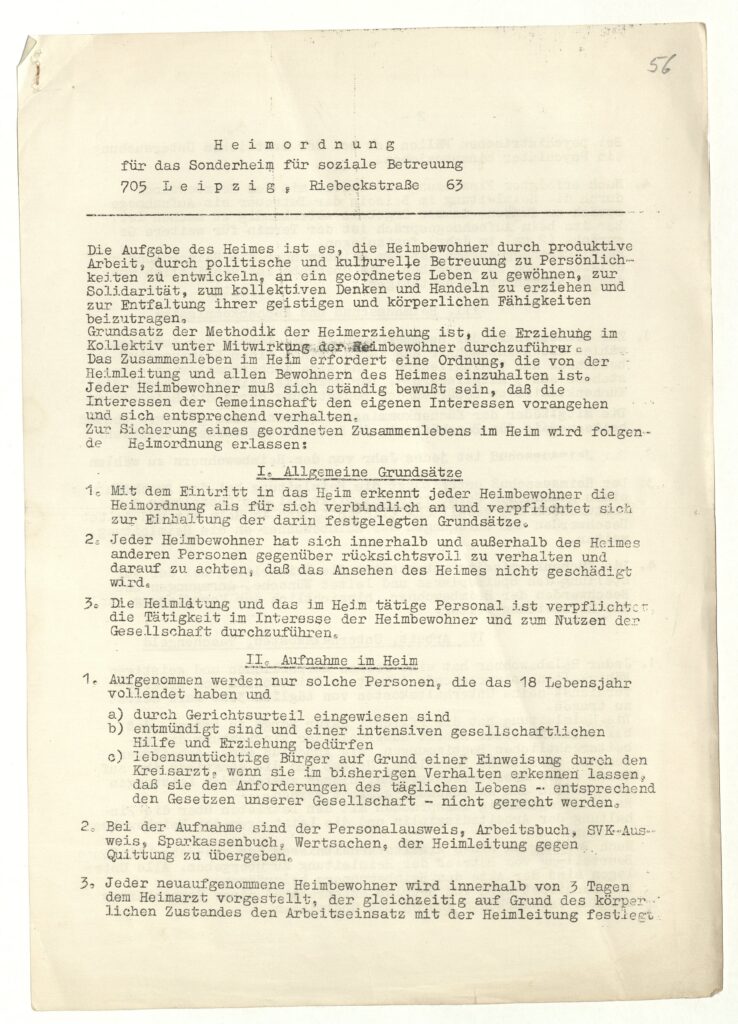

The Leipzig city archives contain two Home Regulations for the Special Home for Social Care, which provide more detailed information about the purpose of the home and everyday life there. The first is only two pages long and cannot be dated, but it can be assumed that it predates the second. The second, presented below, is much more detailed at six pages and came into effect on August 1, 1968.

At the beginning of the Home Rules, the mission of the Home is mentioned. These included “developing the residents into personalities through productive work, political and cultural care, accustoming them to an ordered life […] [and] educating them to think and act collectively […].”[8] The idea of “education through work” is clearly in the foreground here; this measure, also known as “work therapy,” was also carried out in other homes in the GDR home system.

The following points were set out in the Home Rules: General principles, admission to the home, home committee and kitchen commission, work, maintenance costs and pocket money, health care, order in the home, daily routine, going out and vacations, educational measures, complaints and dismissals.

Only adults who had been committed by court order, who were “incapacitated and in need of intensive social help and education”[9] or who were considered “citizens unfit for life”[10] were admitted. The 1968 Home Rules also stipulated that residents had to work according to their physical and mental abilities. This could take place in a workplace outside the home. Residents had to pay a maintenance fee of 3.80 ostmarks from their own earnings. The salary was not paid to them, but transferred to the home’s account. The residents received pocket money from this, the rest was saved and transferred to them when they were discharged.[11]

The daily routine was strictly regulated and the residents had to follow it. There was no right to leave. However, it could be requested and granted for “good behavior”. According to the Home Rules, inmates were not allowed to leave during the spring and fall fairs. These precautions served the purpose of keeping the city “clean” of so-called “antisocial” people in order to present a positive image to the West, among other things. The euphemistic term “educational measures” includes punishment methods such as isolation after working hours and “placement in an isolation room”.[12]

Overall, the Home Rules show parallels to processes in other homes (such as the strict daily routine or the methods of punishment) that were part of the GDR home system, such as the closed venereological ward, which, like the special home, was located on the site of Riebeckstraße 63. In addition, the Home Rules show continuities – across political systems – to the former work center on the grounds of Riebeckstraße 63, such as the idea of “education through work”.

Bettina Wilpert

Footnotes

1. Interview mit Thomas Müller geführt von Bettina Wilpert

2. Zimmermann, Verena: Den neuen Menschen schaffen: Die Umerziehung von schwererziehbaren und straffälligen Jugendlichen in der DDR )1945-1990), Köln: Böhlau 2004, S. 226.

3. Zimmermann, S. 227.

4. Zimmermann S. 225ff.

5. Brüning, Steffi: Prostitution in der DDR: Eine Untersuchung am Beispiel von Rostock, Berlin und Leipzig, 1968 bis 1989, Berlin: be.bra wissenschaft verlag 2020, S. 60.

6. Brüning, S. 60.

7. Interview Müller

8. StAL: HsozB, Nr. 788, Bl. 56f.

9. StAL: HsozB, Nr. 788, Bl. 56.

10. Ebd.

11. StAL: HsozB, Nr. 788, Bl. 56ff.

12. StAL: HsozB, Nr. 788, Bl. 58f.